From Chicago to Finland: A Journey

Somewhere in northern Finland, November 2015

The sun slowly crept behind my head, its morning rays prickling my neck. The air breezing around us was dry and chilly. Each breath I took felt simultaneously dehydrating and frigid. I glanced at the scraggly forest of trees lining the road and looked down at my phone. I peered at the blue dot supposedly indicating where I was. I found that it believed I was still in Oulu, a city I had left nearly an hour ago.

Sighing, I looked up at my friend Aatash with a frown.

We were lost.

The two of us were trudging along Metsokangas, a small town in northern Finland. Or at least that was the plan. Instead we found ourselves lost in the Finnish countryside. Aatash and I were looking for Metsokangas Comprehensive School, a Finnish public school with around 1000 students. We had scheduled an early morning meeting with Kalle, the gregarious principal who had responded to our requests for a tour.

However instead of finding ourselves in the town of Metsokangas, our inept navigation caused us to get off at the wrong bus stop. When we discovered our mistake, we tried to head back the way we came, knowing that the correct stop would be somewhere on the path.

We were surrounded on all sides by clumps of tall and skinny trees that tapered off sharply, appearing as bundles of upright green needles. Unfortunately, the uniformity of the landscape left us few landmarks to work with. We weren’t sure which way to go.

As I glanced at the barren fields around us, I thought back to the chain of events that to this point.

Seven months earlier. In my apartment in Chicago, Illinois. April 2015.

I clicked “Send” on the email I had spent hours writing and rewriting, pushed back my chair and got up to stretch. My lips felt dry and my heart drummed an erratic staccato.

There. I had done it.

After a quick gulp of water, I anxiously opened my “Sent” folder to reread the email I had just delivered. My eyes darted over the lines of text.

Hey Emma,

Carl here. I just wanted to shoot you a note that, unfortunately, after some introspection, I decided that going back to school wasn’t exactly what I wanted to do this year.

That’s a shame because I’m sure I would have had a blast in both the MS program, and in learning about the ways to get involved in CMU educational projects, like yours. Nevertheless, there are other things I want to explore before making a decision to return to school.

I also plan on continuing honing my skills in service of making a difference in parts of the world that I care about, education included, so I sincerely hope that our paths may cross again.

Best, Carl

As I reread my email to the professor who could have been my advisor, I wasn’t only trying to confirm that I had sent it. I was also taking a last glance over the shoulder at the road not taken. Rereading this email was the final regret-tinged look at the choice I didn’t make, as if by poring over each word in my email I could peer into the hazy Multiverse of Could-Have-Beens, hoping to catch a glimpse at other futures I might have had.

I was rereading my email to grapple with the question I guess many people spend much of their lives untangling: did I make the right choice?

After all it was only a month earlier that I had yelped with joy and surprise when I had received my admissions letter to Carnegie Mellon University’s Machine Learning department. This department was founded in the late 1990s and was the first in the United States to focus on the field of machine learning. Many important discoveries in the field of machine learning had been made there. Over the years the department graduated a number of notable alumni who now held significant roles within academia and industry.

I had even received a scholarship, which both surprised and thrilled me.

The honeymoon period lasted a number of days. But the triumphant confidence in knowing what I would be doing for the next few years slowly began to trickle away. Instead, a gnawing discomfort crept into my mind. After all, why was I so interested in going to graduate school in machine learning? It wasn’t an option that had been on my radar even just six months prior.

Slowly but surely, a batch of doubts were beginning to simmer in my head.

I remember sitting home one day in March, trying to wrap my head around the doubt I was beginning to have around my decision to enroll in graduate school. Why had I chosen to go to graduate school? Was it what I really wanted to do? It was the fact that I was now willing to ask these questions that were causing the pangs of self-doubt. The truth was that I had actually opportunistically stumbled my way into being accepted into graduate school. I had been working in a position where most of my coworkers had at least a Masters, with a number of them with PhDs. That environment, combined with the unquestioned belief that more education and credentials are a “safe” or “correct” choice, gave me career myopia.

Don’t get me wrong. I had reasons for getting a graduate degree in machine learning beyond acquiring additional credentials. While I was applying to graduate school I was part of a program called the Data Science for Social Good Fellowship (DSSG). Through DSSG I worked as a data scientist in Chicago, where I collaborated with nonprofits and school districts to use my background in statistics and computer science to solve organizational challenges.

In this role, I noticed how valuable my technical background was to the social sector as there was a dearth of technical professionals applying to work with nonprofits or governments. If I built upon my technical abilities by getting another degree in machine learning, I reasoned that could make even more impact.

Thus the immediate rewards of getting another technical degree seemed obvious. The costs appeared negligible. The burden of proof had sneakily crept from a positive one to a negative one: from “Why should I go to graduate school?” to “Why shouldn’t I?”

From that point on, I was on a one-track mind of getting accepted to graduate school, focusing my attention on how to optimize getting accepted, rather than understanding what I wanted out of my life or career.

But just as in love, any relationship cobbled from momentary infatuation may have an initial sharp peak, but also, in inevitable symmetry, also a steep plummet. My fling with graduate school was simply that: a fling. The initial euphoria I experienced couldn’t conceal the cracks between me and Carnegie Mellon: I didn’t think I wanted to continue working as a data scientist, I didn’t know what I’d use my degree towards, I hadn’t explored other career options to learn if getting a graduate degree was necessary or valuable.

During this period of self-doubt, I drew inspiration from my friend Cindy’s courageous decision to decline her offer to Harvard Medical School. After confronting an uncomfortable truth — that the career she and her parents had spent years preparing for wasn’t what she wanted — Cindy turned down Harvard with no other opportunities in hand.[1] Her decision to trust herself and plunge into uncertainty emboldened me to take my own leap of faith.

It became clear to me that attending graduate school was something I decided on without deliberate reflections on my goals, values or passions. These underlying bedrocks of commitments weren’t there. I didn’t want, need nor even particularly like the idea of more formal schooling.

And just like that, it was over.

So then, what was next?

Somewhere in northern Finland, November 2015.

I was relieved.

After 35 minutes of wandering, Aatash and I finally found ourselves back on the main road. Or at least that’s what we suspected. Google Maps hadn’t been particularly cooperative when we asked it to pinpoint our exact location.

The entrance to Metsokangas Comprehensive School

As practicing statisticians and data scientists, we thought of no better way to decide this than to run a large-scale experiment. The following section details exactly what we tested and discovered.

Nevertheless, we could now see buildings poking over the gangly forestry around us. As we progressed towards these beacons, we were filled with hope. There was one building in particular that stuck out. It was too large to be a home, and too garishly colorful to be an office building.

Our confidence increasing with every step, Aatash and I prepared ourselves for our first look inside the heralded Finnish education. We were excited. In education circles, Finland’s education system is often lauded as a model to emulate. Finnish students consistently scored near the top of international exams, and teaching was regularly seen as a highly desirable profession for ambitious Finns to pursue.

As we came closer to the building, we could tell that it was indeed what we had been looking for. We had found the Metsokangas Comprehensive School.

We had finally arrived.

Four months earlier. In Berkeley, California. July 2015.

In the months following my decision to decline graduate school, I wrapped up my Fellowship and headed back to the Bay Area. Technically I was working a summer job as a data scientist at an enterprise machine learning startup. But it was really simply an internship I had taken when I was still convinced that I was going to need a summer internship to bridge my Fellowship and starting graduate school in the fall. Now that my fall had been drastically altered, I needed to figure out what I would be investing my time and energies into instead.

When I was in Chicago, I had kept in touch with a few friends of mine that I had met while in college. One of them, Aatash, had been my roommate my senior year. The other, Andrew, had been introduced through a close mutual friend.

When I landed back in the Bay, I got a chance to meet up with each of them individually.

Over a meal of Asian-fusion tacos in Oakland with Aatash, I learned from him that he had recently left his job. When we sat down, he plopped down a thick copy of Diane Ravitch’s The Life and Death of the Great American School System on our table. I had heard of Diane Ravitch and her numerous books. Her critical, and oftentimes controversial, stances on the modern wave of education reform was something I loosely remembered encountering in a few college courses.

“Why are you reading this book on education history?” I asked, my interest piqued.

Aatash grinned at my question, as if expecting it. He replied that after leaving his job, he’d become increasingly interested in deepening his knowledge of the US K-12 education system. This book was just the latest in a series he’d be reading.

Now, this wasn’t completely out of the blue. Aatash and I became close friends in college in part due to our shared enthusiasm for pursuing a career in education. We had quickly become friends over excited and idealistic conversations. The fact that we were also both diehard NBA fans didn’t hurt.[2] (A few years ago I wrote an article that explained how I ended up becoming inspired to work in education. You can read it here.)

But that day in Oakland, over a meal involving copious amounts of spicy glazed pork belly, we found ourselves again discussing the same issues and interests that had brought us together the first time we met. It became clear to us that with extended time on our hands, there was a way to take these shared passions and work on them together.

As we chatted over the meal, I brought up what I had heard from our mutual friend Andrew. After graduating from college, Andrew deliberately chose to hold off on the rat race of job hunting.

Instead, Andrew spent time rigorously researching different areas that seemed to hold potential for social impact — criminal justice policies, campaign finance reform, global warming, to name a few — and tried to evaluated which field he could make the most difference in. It just so happened that when I had flown back into the Bay, Andrew was beginning his investigation into the field of education.

When I told this to Aatash, the two of us wondered whether there was some way we could team up with Andrew. The three of us could come up with the topics in education we each wanted to learn about, the books we wanted to read, and the organizations we wanted to visit.

As we shared ideas, I remembered something.

When I was writing The Data Science Handbook, I had interviewed a data scientist named Clare Corthell.

She had created her own “Open Source Data Science Masters” as a way to switch careers from product design into data science. She quit her job and spent 6 months reading textbooks, taking online courses and building projects to learn the skills required to become a data scientist.

Her story received a wide amount of attention, especially after she successfully eventually landed a job as a data scientist. Her tale made me think that something similar could be done for education.

And thus, the Self-Guided Masters in Education was born.

Finally at Metsokongas Comprehensive School in northern Finland. November 2015.

Soon after arriving at Metsokongas Comprehensive School we met with Kalle, the school’s energetic principal. He eagerly led Aatash and me through a tour of the school’s campus, explaining that we were simply one of the many groups that have visited Metsokongas this year. After Microsoft named the school a “Showcase School”, a recognition given to schools that are “intentionally redesign[ing] learning spaces … [and] driv[ing] personalized learning”, Kalle found hordes of admiring visitors from around the world beating on his doors. Aatash and I were simply the latest wave.

As he explained this to us, we took in the sights around us.

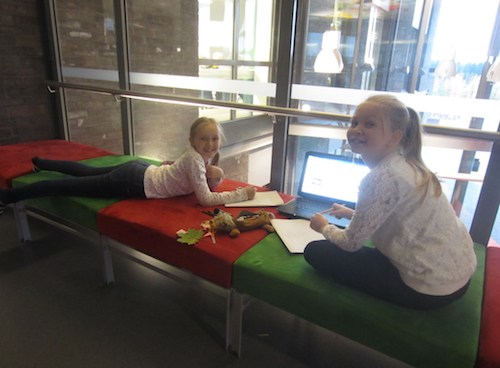

Students working in the hallways of Metsokangas. Photo Credit: Building Community Bridges

We found students lounging in the hallways, idly chatting with friends as they worked on assignments. When Aatash asked why so many students were working outside of a classroom, Kalle explained to us the school’s philosophy of encouraging students to work in comfortable areas and positions, rather than boxing them within orderly classrooms.

As we walked through the facilities, Aatash and I noticed that nearly all the classrooms could be connected, simply by folding in the collapsable wall partitioning two rooms. Kalle told us that the idea was to encourage greater interdisciplinary collaboration between different classrooms. In addition, unlike most classrooms in the United States, each class we visited had two teachers. One could teach while the other walked around classroom, gently shushing or encouraging as they went around. This effectively halved the student-to-teacher ratio. I was surprised by this co-teaching approach, having never seen it before.

During my visit, one particular memory of visiting a 7th grade Home Economics course stands out. I remember blinking in surprise as I entered the classroom. Many of the young students were wielding large cutting knives. They stood around a kitchen listening diligently as a teacher explained something in Finnish.

“They’re going through the cooking unit right now,” Kalle whispered to me. I gaped at him, dumbfounded at the level of trust and responsibility these students were given. He grinned at the look on my face.

“Home Economics is a mandatory course for all Finnish students. Students learn about nutrition, budgeting, cooking and many other topics that we think you need to know.”

As we left the classroom I marveled at the trust these students received — imagine the uproar if a group of American 7th graders were using sharp knives as part of a course — as well as practical curriculum of the Finnish system.

Throughout the tour, Aatash and I got a chance to speak with students, teachers and administrators. We learned about its history, funding, pedagogical approach and school organization. We even got to play with some of the students during one of the breaks.

By the time the visit was over, Aatash and I felt utterly stuffed full of experiences to later digest and ruminate. We had chosen to visit Metsokangas Comprehensive School as part of our tour of the Finnish school system, hoping to see some of the best that Finland had to offer. We were not disappointed.

A comprehensive analysis of all that we learned in Finland will be saved for a future article, but I’ve listed some of the highlights below:

-

Little standardized testing: Finnish students famously score near the top of international assessments in math and science. Yet students in Finland are rarely assessed on standardized tests. This runs contrary to the high-stakes testing that the American accountability movement is pushing, demonstrating that it’s possible to build a high-performing education system without loads of testing.

-

Professional autonomy: As a result of the lack of testing, a culture of professional autonomy is created for teachers, as there isn’t a constant threat of removal due to students’ performance on tests.

-

More responsibility: The Finnish curriculum trusts students with a greater degree of responsibilities much more frequently than US culture, with the Home Economics story from above being a great example.

-

Special education: In Finland, nearly 50% of students are classified as “special learners” at one point or another. Unlike Americans, who have long maintained a culture of stigma against “special education”, however, Finns don’t see being a “special learner” as something negative. Many more students in Finland receive special education instruction, which is categorized differently from that of the US. The label is not necessarily related to a developmental disability or physical disability; rather, it refers to any sort of difficulty with regard to learning reading and writing, mathematics, or foreign languages. Students who are classified as being “special learners” receive extra tutoring and support to help them catch up.

Aatash and I near Metsokangas. We definitely didn’t pick the best lighting for this photo.

The Self-Guided Masters in Education. Present time.

As Aatash, Andrew and I planned our curriculum for the Self-Guided Education Masters (SGEM), we decided to visit Finland. Finland’s education system is commonly lauded in education circles as, within the span of 50 years, it leapt to become one of the highest-performing national systems in the world.

One of our goals during the SGEM was to investigate what makes for a “high-performing education system” and why countries like Finland had one.

We also created the SGEM to structure and explain what we were doing to our friends, parents and other curious individuals. It contains a list of books, “capstone projects” and topics we wanted to learn. We even put up a website describing what it is, what our goals are and why we chose to do this rather than go through a more traditional Masters degree. If your curiosity has been whetted and you want to learn more, you can check out the website at www.understanding.education (it’s quite the domain, right?).

The three of us who created this program are hoping to use it as a way to structure what we wanted to learn and work on. For example, we recently submitted a proposal for a project-based learning high school to a national competition, and we’ll also be putting online a “Master’s thesis” that synthesizes what we’ve done and learned.

Our goal in creating the Self-Guided Masters in Education is to use it as a compass to point us in the direction of where we want to spend the next few years of our lives. Would it be to launch a school? Create a company or nonprofit? Or should we become teachers, or even work in a district’s central office?

As of right now, just as it was in northern Finland, our exact destination isn’t clear. The future is still hazy and blotted with unanswered questions, but I can’t help feel that I made the right choice in creating my own path rather than attending Carnegie Mellon.

By pursuing an independently created curriculum rather than entering a formal graduate program, I’ve found myself more comfortable with uncertainty with each passing day. Through the SGEM, I’ve also found myself starting from “square one” in asking myself the hard questions: what drives me? What are my long-term life goals? What do I value?

These are the sorts of thoughts that I didn’t typically find myself having the space to think about when I was working. Or if I happened to think them, I usually relegated them to the bucket of “Things That Are Important But Not Urgent” and always found a reason de-prioritize answering them lower than any immediate tasks.

However, by deliberately carving out space in my life for unstructured thinking, I’ve been probing deeper into what I want out of life.

Through this probing, one of the conclusions I’ve come to in the past few months is how important it is for me to align my job with my core identity. My past jobs as a data scientist and project manager paid well and were high-status professions, but I felt uneasy with them both because I didn’t identify strongly as a “data scientist” nor “project manager.”

Pursuing another technical graduate degree that would have been taking another step down a professional path in technology. But why deepen into a career that didn’t fit who I am?

Instead, I feel a greater sense of identification with descriptions like “educator” and “teacher” and believe my next job will be more aligned with these terms. As a result of these nuggets of self-knowledge, I’ve become increasingly confident that the next job I take will be more authentic to my identity and goals.

During the first few months of pursuing the SGEM, I felt a great deal of confusion, anxiety and self-doubt. What if I made the wrong choice by turning down graduate school? Who in the world makes up their own “masters” degree? What if this was all a half-baked idea and a waste of my time?

I remember feeling similarly afraid and anxious when I was lost in the Finnish countryside, on my way to Metsokangas.

But over time, these feelings of against about my professional decision peacefully disappeared. They were replaced by a calm confidence in this journey. Where does this confidence come from? It stems from one very simple fact: despite not enrolling in a graduate school, I’m finding myself learning more than ever.

Thus I believe that, just like in Finland, I will eventually find my way.

Footnotes

[1] You can read more about Cindy’s story in the first chapter of my book, College Uncensored. Her story is worth a read.

[2] Unfortunately, Aatash’s favorite team is the Los Angeles Lakers. But hey, nobody’s perfect!