Weeks 7-12: Summer Wrapup

This is the final post in a series of posts chronicling my reflections on participating in the 2014 Data Science for Social Good Fellowship at the University of Chicago. While I had intended to post once a week, I ended up falling short of my goals. Work from DSSG piled up, making it tough to write thoughtul posts on a weekly schedule.

Nevertheless, I intend for this to be a wraup post that summarizes the work that my team and I did. Reading this will allow you to glean all the different experiences, learnings and findings I encountered over the summer.

You can read my last post here:

To get automatically notified about new posts, you can subscribe by clicking here. You can also subscribe via RSS to this blog to get updates.

-> <-

<-

->“It is health that is real wealth and not pieces of gold and silver.”<- ->- Mahatma Gandhi<-

##Introduction President Obama’s Affordable Care Act enacted broad reforms across the United States’ healthcare system. While the healthcare landscape has changed drastically, one important constant has remained the same: a person’s health is affected significantly by non-medical factors.

For example, a patient with an asthmatic condition caused by a moldy apartment will not be cured simply with better medicine. She needs a better apartment, and yet our health care system is not traditionally set up to handle these non-medical issues.

During this summer’s DSSG Fellowship, our team – Chris Bopp, Cindy Chen, Isaac McCreery, myself and mentor Young-Jin Kim – worked with a nonprofit called Health Leads to apply data science to address these non-medical needs, to help patients get access to basic resources vital for a healthy life.

##Health Leads In 1996, Harvard sophomore Rebecca Onie was a volunteer at Greater Boston Legal Services, assisting low-income clients with housing problems. She found herself speaking with clients facing health issues brought on by their poverty. Some lived in dilapidated apartments, infested with rodents and insects. Others couldn’t afford basic necessities like food. Modern medicine was largely ineffective against these issues. Doctors were trained to treat medical ills, not social ones.

Inspired by her experiences, Rebecca launched a health services nonprofit called Health Leads, which recruits and trains college students to work closely with patients referred by doctors who needed basic resources such as food, transportation, or housing. These college students, called “Advocates” in Health Leads lexicon, learn about each patient’s needs, and meticulously dig up resource providers – food banks, employment opportunities, childcare services – that can fulfill them.

In the nearly two decades since Health Leads’ inception, its impact on the health landscape has been tremendous. In 2013 alone, Health Leads Advocates worked with over 11,000 patients to connect them with basic services and resources.

##The Problem

Serving a predominantly low-income patient population can pose a challenge for Health Leads. Some patients will lack stable, permanent housing or employment. Others may not own a cell phone on which they can be consistently reached. Health Leads noticed that these circumstances affected their work with some patients: despite Advocates’ best efforts, a proportion of their clients would disconnect from working with the program. These clients would be unreachable, not returning phone calls and ultimately Advocates would be forced to close their cases – never knowing if these clients received the basic resources they needed.

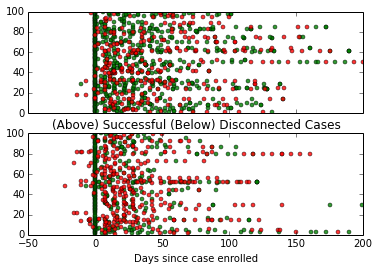

Below is an image displaying the phone calls made to a random group of 200 different patients and whether they responded or not. Half of the clients worked with Health Leads through the completion of their case and the other half ultimately disconnected from Health Leads’ program.

-> <-

<-

(The cases with negative days are ones where Health Leads took down the information for patient, didn’t begin working with them until a few days later.)

Just at a glance, there appears to be pretty clear differences between the two groups. Most obviously, the disconnected patients seem to have many more failed communication attempts (red dots) than successful ones (green dots).

However, Health Leads wanted to know: exactly what are the factors that contribute to a patient disconnecting from Health Leads? How does the difficulty of a patient’s need play into the problem? What other factors might be important to consider?

Against the backdrop of these pressing questions, Health Leads came to our DSSG team to use data to help discover some answers.

###The Challenges

When we began tackling the problem, we ran into a slew of challenges. Unlike in the internet world where companies can track every iota of data down to the click, nonprofits serve their clients in person – meaning data must be manually recorded, rather than passively accumulated.

Furthermore, it may be that the factors we end up discovering as influencing patient outcome may be outside of the control of Health Leads. What if we found that the most significant indicators of patients’ success was gender or age? It would be hard to translate a finding like this into operationalizable actions for Advocates.

##Our Findings

Over the summer, our team worked through the data to distill insight, discovering findings that Health Leads can use to improve their practice.

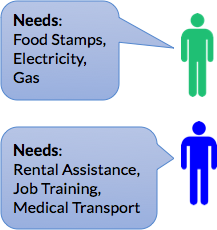

For example, we developed a “Patient Complexity Index” that tries to capture the probability that a patient will disconnect from Health Leads. We incorporate information about the type of resources this patient requires and historic performance information about the Health Leads clinic where the patient is served. For instance, needs involving employment or housing are typically much harder to resolve than needs around childcare or transportation. The success rates of each of these resource connections also vary per desk. We found that different Health Leads sites specialize in different types of resource connections.

By combining this information, Health Leads can more accurately quantify the difficulty of each patient so that more experienced Advocates can work with patients with more complex needs. By doing so, Health Leads can better address each patient’s different circumstances, lowering the chance that they’ll disconnect.

-> <-

<-

->A Need Complexity Index can help quantify the difficulty of these patients’ needs<-

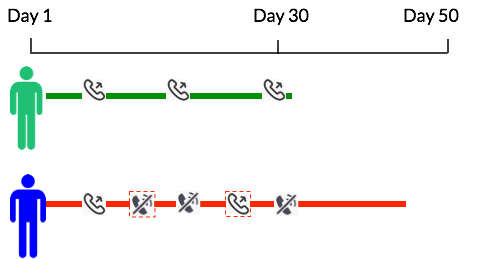

Furthermore, Health Leads currently standardizes the intervals at which patients call patients: a minimum of once every 10 days. The findings from the data confirmed previous Health Leads research that Advocates should try to get in touch with patients frequently in the beginning stages of building a relationship with a patient. When an Advocate successfully contacts a client in the first month, that one successful phone call significantly decreases the likelihood of disconnection:

-> <-

<-

->Health Leads should call new clients frequently in the first month<-

###Conclusion

We presented our findings and models to Health Leads at the end of this summer, and our results validate Health Leads’ emphasis on regular follow up. We believe that the information we provided reinforces organizational strategies that can increase client engagement: calling clients regularly and leveraging communication tools such as text messaging. By investigating the different factors influencing a patient’s likelihood to disconnect, our team’s findings have pointed to important steps that Health Leads can continue to take to ensure that more people get the resources they need for a healthy life.

I write about data science applied to social causes. If you want to be notified when my next post is published, subscribe by clicking here.